Walter Rauschenbusch was the eighth in a line of pastors and started his career serving a small church of immigrants in New York City. He saw firsthand the impact of poverty: overcrowding, high rents, low wages, horrendous working conditions, vulnerability to weather and disease. He realised that in order to serve the spiritual needs of his congregation, he would have to address their whole lives.

Walter Rauschenbusch was the eighth in a line of pastors and started his career serving a small church of immigrants in New York City. He saw firsthand the impact of poverty: overcrowding, high rents, low wages, horrendous working conditions, vulnerability to weather and disease. He realised that in order to serve the spiritual needs of his congregation, he would have to address their whole lives.

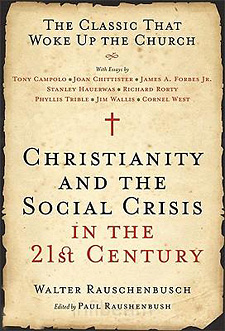

So he turned to the Bible, and wrote a series of essays that became Christianity and the Social Crisis. His breakthrough concept was to recognise the Kingdom of God as the centrepiece of Jesus' teaching and the hope of his ministry on earth.

In contrast to the society around him, which Rauschenbusch saw as resting on coercion, exploitation and inequality, Jesus found a kingdom based on love, service and equality.

The book was released 100 years ago, and was an immediate success, a bestseller for three years. As a consequence denominations began incorporating social justice principles as part of their Statements of Faith. It also empowered reforms including child labour laws, minimum wage declarations and President FDR's New Deal. Martin Luther King Jr credited the book as having influenced him in developing a theological basis for the push for civil rights.

Rauschenbusch’s book pushed not just for personal repentance, but societal repentance and national regeneration. It attempted to bridge the gulf between emphases on personal holiness and social justice.

Walter's great grandson Paul recognises the same disconnect as relevant today, and has collected essays from leading scholars that are included. There is much affirmation, some contemporary examples and updating, and also some constructive criticism:

"¢ Phyllis Trible warns against his elevation of the prophets without recognition of the social concerns of the creation story, the law, the historical narratives, and the wisdom literature.

"¢ Tony Campolo points to a possible focus on Jesus as human rather than Lord, and the temporal rather than the eternal; as well as recognition of personal and social sinfulness requiring radical transformation.

"¢ Stanley Hauerwas asserts Rauschenbusch was too dismissive of the church's potential to transform society.

On the other hand, Rauschenbusch is recognised as being prophetic in his warning of the widening gap between rich and poor, and the danger that the church's social reformation agenda could be compromised politically by a focus on personal morality. He spoke against Christians being complicit with materialism, or excusing social sins such as corporate greed or misuse of political power.

Unfortunately, many have embraced the social gospel at the expense of biblical authority and acknowledgement of personal sin, and Rauschenbusch has also been associated with liberalisation of Christianity.

However, this is a very useful book, with essays critiquing and complementing the original text. The result is to reinforce the biblical social concerns of God; to challenge us to personal change and a social vision; to critique the role of the church; and to be amazed afresh at how the towering presence and message of Jesus is relevant to all contexts and generations.